A companion piece to episode 95: The Once and Future King, written by Laurel Hostak

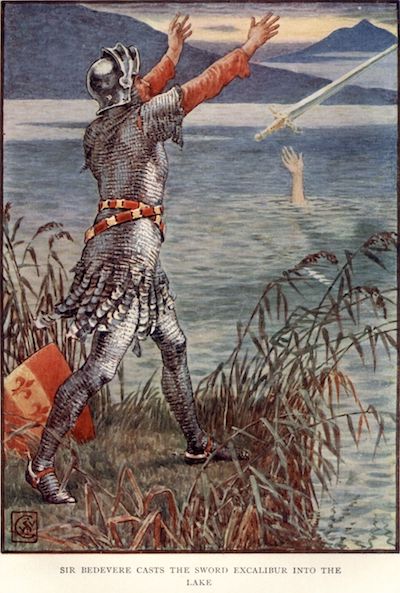

Walter Crane

The Blades of King Arthur: The Sword in the Stone, Excalibur

You know the story of Arthur and his legendary sword. An orphan boy is raised by Sir Ector and serves as squire to his adopted brother Kay. His youth is perfectly ordinary, until the day he accompanies Kay to a tourney and loses his brother’s sword just before he’s about to ride into combat. On this day, in desperation to replace the sword, Arthur instinctively pulls a sword from a stone, and the course of his life—and his nation’s—changes forever.

The sword he draws from the stone is more than a weapon for combat or tournaments. It’s the very symbol of sovereignty that guarantees the boy’s royal destiny. This child will become the greatest king of Britain. He will welcome a golden age. He will ignite the hearts and minds of mankind for centuries to come.

The sword in the stone is one of the most unique and enduring symbols in the Arthurian legend—which says a lot, given the story is sweeping, epic, and littered with magical and significant objects. In contemporary adaptations of the legend, this sword is called Excalibur, though the preponderance of Arthurian texts from the Middle Ages will affirm that Arthur has two magical swords. He pulls one from the stone, and is later given Excalibur by the Lady of the Lake. Whether to avoid confusion or to enhance narrative cohesion, Hollywood and modern writers have overwhelmingly chosen to combine the two blades, and thus combine the concepts of powerful bloodline and military might.

Despite the sword in the stone’s imprint on the collective consciousness and association with Arthur’s upbringing, it’s Excalibur that’s first introduced to the legend. It appears under the Celtic name Caledfwlch in the Welsh prose tale Culhwch and Olwen (collected in the Mabinogion in the 12th century). In the same century it will materialize in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s blockbuster Latin treatment of the legend in his Historia Regum Brittaniae—or History of the Kings of Britain—as Caliburnus. The French tradition will give us the name Escalibor, and our friend Chretien de Troyes describes the sword by its ability to cut through steel and iron. Interestingly, it’s French writer Robert de Boron, who is best known for his continuation of Chretien’s unfinished Perceval, the Story of the Grail, who will introduce the sword in the stone motif for the first time in his poem Merlin.

Walter Crane

Excalibur has several recognizable attributes that appear in multiple sources. In addition to its uncanny ability to cut through just about any material, it’s also blindingly bright. As Sir Thomas Malory writes in his landmark Le Morte D’Arthur, "thenne he drewe his swerd Excalibur, but it was so breyght in his enemyes eyen that it gaf light lyke thirty torchys." Perhaps most importantly, the scabbard bestowed on Arthur along with the sword stops the bearer from losing blood in battle. In Malory, Arthur’s half-sister Morgan le Fay will steal the scabbard from him, allowing Mordred to deal the death-blow upon him in the field.

The Sword of Gryffindor

Spoilers for the Harry Potter series

Swords of power don’t originate in the Arthurian legend—in fact, we see them in Norse and Greek mythology, folklore surrounding Julius Caesar and Ancient Rome, and even the Bible, in which a cherub wielding a flaming sword prevents Adam and Eve from returning to the Garden of Eden. But it’s impossible to overstate the importance of Arthur’s legacy on Western storytelling tradition, and I’d like to spend some time examining the intersection of these particular magical objects with contemporary popular culture. If you have any familiarity with the books or movies of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, you’ve probably made the connection at some point between the sword in the stone and the sword of Gryffindor.

Much like the sword Arthur pulls from the stone in a churchyard—the one that can only be retrieved by the true king/heir to Uther Pendragon—the latter sword manifests only to a worthy Gryffindor. In a time of need, it materializes inside the Sorting Hat. This happens twice during the series as we witness it, appearing first to Harry as he’s confronting a Basilisk in the Chamber of Secrets, and later to Neville Longbottom during the final battle against Voldemort and his Death Eaters. In both instances, the sword is used to defeat a snake or serpent-like beast who is the servant of Voldemort and symbol of Slytherin house. Voldemort is the heir of Slytherin, a literal descendant of the Hogwarts co-founder’s line, and his life is tied to the snake’s in both cases, making the sword instrumental in severing his own lifeline. What’s interesting about this double-appearance of the sword to different characters, though, is that it suggests a slight departure from the hereditary or divinely-ordained nature inherent in the medieval tradition. Rather than choosing a king, a sovereign who is the offspring of the royal line, the sword chooses a champion who becomes a symbolic heir of Gryffindor. That hero then defeats a literal heir of Slytherin. The Harry Potter series repeatedly affirms the presence of free will and choice in its universe, so this more egalitarian expression of the sword in the stone motif brings home the idea that anyone can become a great hero.

Neville Longbottom severs the head of Nagini, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, pt 2

Harry Potter, like the Arthurian legend, is densely populated with magical objects. From the Remembrall and the Golden Snitch to the Goblet of Fire and the Deathly Hallows themselves, Rowling is hyper-aware of the lengthy folkloric tradition each of her objects alludes to. And Rowling is clearly interested in the magical mysteries of Arthur. Not only does she give us the obvious connections between legendary swords, but her most prestigious wizarding characters signify their adeptness by their rank in the “Order of Merlin.” With that, she unequivocally tells the reader that the legends of Merlin, Arthur, and his knights are real in this story universe. But regardless of historicity in- or out-of-universe, the symbolic link is powerful. Let’s not forget that Harry will eventually marry Ginevra “Ginny” Weasley, whose first name is a derivative of “Guinevere.”

There’s a third appearance of Gryffindor’s sword, chronologically in between the two Sorting Hat revelations, in which it reveals itself to an on-the-lam Harry at the bottom of a pond. Placed there by Severus Snape, it gives Harry his first fighting chance at destroying horcruxes and eventually defeating the Dark Lord. At once, the image of the sword glowing at the bottom of a pool of water evokes not just the bestowal of Excalibur by the Lady of the Lake, but the appearance of the grail to Perceval. The Holy Grail has additional analogs in Harry Potter in the form of the Goblet of Fire, the Triwizard Cup, and the Hufflepuff goblet that serves as a horcrux—or truly, any hallowed object that is the subject of a long and arduous quest. Turning to the Deathly Hallows—the Resurrection Stone, the Invisibility Cloak, and the Elder Wand—we have further Arthurian links. The unbeatable wand echoes Excalibur as the weapon of choice for wizards, the cloak denotes the magical scabbard, and the stone once again corresponds to the grail or to Arthur’s rumored healing and rebirth on the Isle of Avalon.

Narsil, the Sword That Was Broken

Spoilers for the Lord of the Rings series

The shards of Narsil at Rivendell

In Malory’s text, the sword in the stone that grants Arthur his divine right as king doesn’t last long. In his first battle, Arthur breaks the sword and seeks a replacement. Merlin leads him to the Lady of the Lake, and she gives him both the sword and its enchanted scabbard. This motif of the shattered sword symbolizes the end of Arthur’s childhood and initiation into a new phase—for himself and for his people. We’ll see the shattered sword image recur time and again in contemporary fantasy literature, most notably in J.R.R. Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings saga.

It’s Narsil, the sword of King Elendil used against Sauron during the War of the Last Alliance, that fulfills the motif. Its name refers to “red and white flame,” symbolizing the Sun and Moon—the “chief heavenly lights, as enemies of darkness.” In battle against the Dark Lord Sauron, Narsil shatters, and Elendil’s son Isildur picks up the shards to cut the Ring of Power from Sauron’s hand. The broken sword and the severing of digits conjure up some pretty blatant phallic references, and these events serve to bring the Second Age of Middle Earth to a close—mankind steps out of its “childhood” into adulthood.

In the Third Age, when we join the story in the Lord of the Rings books, Narsil remains in pieces, waiting for Isildur’s heir to reclaim and reforge it. That heir will arrive in the form of Aragorn, an extraordinarily Arthur-like figure who is destined to usher in a new golden age for the race of men. The blade will be reforged, and Aragorn will give it the name Anduril, the Flame of the West. Its name, like its parent blade, hearkens to celestial phenomena by using an elvish word for sunset. The sun is just dawning on mankind, but setting on the enchantments, magic, elves, sorcerers of the land… those will depart as a new age is born.

It’s just as Robert de Boron wrote in his Merlin:

“...when that knight has achieved such heights that he’s worthy to come to the court of the rich fisher king and has asked what purpose the grail served and serves now, the Fisher King will at once be healed. Then he will tell him the secret words of our lord before passing from life to death. And that knight will have the blood of Jesus Christ in his keeping. With that the enchantments of the land of Britain will vanish, and the prophecy will be fulfilled...”

Lightbringer, the Red Sword of Heroes

Beric Dondarrion wields a flaming sword on HBO’s Game of Thrones

Spoilers for HBO’s Game of Thrones

And while we’re talking about contemporary fantasy and legendary swords, perhaps the pop culture property that gives us the largest bounty is George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire and the television adaptation Game of Thrones. Every major house in Westeros seems to have a powerful sword associated with its history and lineage. Valyrian steel blades are passed from fathers to sons as symbolic of nobility and pedigree, and some carry mysterious and magical myths. Take Dawn, for example, the ancestral sword of House Dayne, forged from the heart of a fallen star and whose bearer is known as the “Sword of the Morning.” Or Heartsbane, the sword of House Tarly, which Samwell steals from its mantle at Horn Hill to affirm his worth.

But there’s perhaps no sword so significant in the story world as the mythical Lightbringer. The sword of Azor Ahai (also sometimes called the prince that was promised), Lightbringer was the weapon that brought an end to the Long Night—a winter that lasted a generation thousands of years before the events of Game. The legend goes that Azor Ahai, a great hero prophesied to fight the Great Other (a devil-like figure in the religion of the Lord of Light), labored for thirty days and nights to forge a hero’s sword. When he went to temper it, however, the sword shattered as soon as it touched the water. So back to the smithy he went, this time laboring for fifty days and nights. Azor Ahai captured a lion and drove the new sword into its heart to temper it; still the blade shattered. The third time, he labored for one hundred days and nights, and, with a heavy heart, summoned his wife Nissa Nissa. To temper the blade, he drove his sword into Nissa Nissa’s heart, and her soul combined with the sword, setting it aflame. This sword would be used to defeat the Others/White Walkers and bring an end to the darkness of winter.

Let’s quickly look back at the quote I shared earlier from Malory’s Morte D’Arthur:

“...thenne he drewe his swerd Excalibur, but it was so breyght in his enemyes eyen that it gaf light lyke thirty torchys.”

Lightbringer, like Excalibur, and to an extent Narsil and Anduril, confronts the carrier’s enemies with a blinding light. And just as King Arthur led his society out of a dark age and into a golden one, Azor Ahai issues in summer after a long winter. The sword—as an extension and symbol of the bearer’s power—becomes inextricably tied to the victory of good over evil, light over dark. Numerous theories exist in the ASOIAF fandom about Lightbringer’s literal or metaphorical origins in the story world. Some say the sword Dawn is Lightbringer, and others claim it’s simply the mantle of the Night’s Watch, or the resurgence of dragons in the world. But always, it’s tied to a great hero and the banishment of a dark age, something we’ve come to associate with Arthur and his knights.

Azor Ahai thrusts Lightbringer into Nissa Nissa's breast. Art by Amok.

Of course, the prophecy in play in the books and television show now is that of Azor Ahai’s rebirth. And here’s where the Arthurian connection truly solidifies. At the end of Le Morte D’Arthur, as in Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Vulgate Cycle, Arthur and his son/nephew Mordred meet on the battlefield and mortally wound one another. Arthur bids one of his knights (either Griflet or Bedivere, depending on the version you’re reading) to cast Excalibur into a body of water. Thus the fair time of Arthur’s reign comes to a close, presumably to be resurrected when a new, worthy ruler steps into focus. Arthur, dying, is ferried off by Morgan le Fay to Avalon, where legend has it his wounds are healed, and he lives on—waiting to rise again in his nation’s hour of need. He is the Once and Future King. It smacks of Biblical resurrection, of course, but also of various national heroes and kings from across cultures. St. Wenceslas lies sleeping under Mt. Blanik in Bohemia, and will awaken when he is most needed to claim the sword of Bruncvik and deliver his country. Finn McCool will rise again to deliver the Irish people, and Holger the Dane will awaken to save Denmark. Even Charlemagne—the bearer of another legendary ancestral sword—will return one day and fulfill his heroic destiny. From the countless examples of this mythological motif, Azor Ahai emerges as an eternal promise.

Lightbringer, Narsil, Gryffindor, and Excalibur are lost to us now, but they wait for a worthy hero to come along, retrieve it, and usher in a new golden age.

Sources

If you enjoyed this blog, check out some of my sources and inspiration! All images are affiliate links, so if you purchase the item, a percentage will go to the podcast. Thank you for your support!