Spoilers for Parts I & II of the Netflix Series ‘The OA’

This week, the long-awaited second season of Netflix’s mind-bending sci-fi/fantasy/magic realism series The OA dropped, and the ending has fans more dumbstruck than ever. Whatever your feelings on the final scenes—or some of the shocking developments of season 2—are, the series continues to flex its unabashed originality, taking some of the most ambitious storytelling risks on television in years.

While season 2 leans more heavily into its sci-fi elements than supernatural ones, the Brit Marling & Zal Batmanglij series remains grounded in potent unconscious imagery and myth. Freshly arrived in a new dimension, the OA/Prairie Johnson’s consciousness lands in the body of Nina Azorova, with whom she shares a birth name and childhood—but whose experience differs entirely from hers after one key moment. In the dimension OA remembers, she had her first near death experience (NDE) when the school bus she was riding crashes, falling into a body of water. She returned from the NDE blind, lost her father at a young age, was adopted by the Johnsons, was held captive by Hap, etc… In the dimension she now inhabits, young Nina never boarded the bus the day of the accident. She had more time with her father, became wealthy and independent, and now dates a Silicon Valley tech mogul. While OA explores her new dimension, season 2 juxtaposes her journey with the boys (and BBA) she left behind and private investigator Karim Washington’s search for the missing Michelle Vu. Sprinkle in some fellow travelers, a sinister dream study, an addictive puzzle game, and a psychic octopus, and you have a deep well of symbolism that builds on the previous installment—adding clarity at times, muddying the waters further at others.

At the center of so many head-spinning plot intricacies is the relationship triangle of OA, Hap, and Homer (in our new surroundings Nina, Dr. Percy, and Dr. Roberts). OA’s jump across dimensions is propelled by her almost magnetic pull toward Homer, a soulmate of sorts. But as another traveler, Elodie, divulges late in the series, it’s not just Homer she’s drawn to, but Hap. Their meetings echo across dimensions as all significant relationships do. These three are locked in an eternal web of desire, attraction, revulsion, dependence… It’s cosmic—the multiverse conspires to bring these three together to enact and reenact the infinite struggle.

The cosmic eternal struggle evokes mythic themes. It brings to mind the cosmology of Norse mythology, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and countless mythological and theological traditions. Gods or forces of good and evil wrestle throughout eternity, one defeating the other before it rises again to continue the fight. As universally as this theme may resonate, within the world of The OA the myth that hits closest to home is the eternal battle between two Slavic deities: Perun and Veles.

A Mythic Struggle

Pagan Slavs worshipped a Pantheon of deities similar to the ancient Greeks or Norse cultures. The most familiar Slavic deity to most of us today would probably be Czernobog (he’s the terrifying winged figure in Disney’s Fantasia, the Night on Bald Mountain segment that traumatized a generation of children; he also appears in the Starz series American Gods based on the novel by Neil Gaiman).

Czernobog in Disney’s Fantasia

But a large subset of Slavic mythology concerns the cyclical battles between Perun and Veles, two opposing forces in the Pantheon. Perun is a supreme god of thunder, lightning, the skies, fertility, and oak trees. His closest equivalent in Greek mythology would be Zeus, and in Norse mythology he corresponds to Odin and Thor. Best known for wielding an axe, Perun is also associated with weaponry made of stone or metal, and is often depicted with an eagle. Veles, on the other hand, is a more earthbound god who represents the forests and water as well as the underworld. If we have to link him with other traditions, we might equate him in some ways to Hades, in others to Poseidon, and in others to tricksters like Hermes or Loki. He’s associated with a host of animals, primarily bears, but is also known as the Lord of All Wolves.

Also like the Norse and various other ancient cultures, Slavic cosmology imagined the known universe as a ‘world tree.’ At its apex, an eagle spreads its wings, representing the skies and the god Perun. At its base, a great serpent is curled around the roots, representing a metamorphosed version of Veles. Etymological evidence suggests that the word or name ‘Veles’ became associated with dragons, serpents, and devils; Veles himself takes the form of a dragon in some myths.

The Slavic World Tree, via Slavorum.org

One version of the enduring myth of the conflict between Perun and Veles begins with the serpent Veles stealing something from Perun (cattle, a wife, or a child). Perun chases the snake around the earth, striking his lightning bolts at the ground and causing Veles to hide. Perun usually succeeds, banishing Veles back to the bottom of the world tree or killing him—only to eventually come back to life and restart the cycle. In other versions of the myth, their struggle is borne out over and over amid great storms, accounting for changing climate conditions in Slavic countries.

Pagan Slavs were eventually Christianized thanks to the efforts of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, but most tribes felt a natural resistance to let go of their native religions and gods, so many traditions were absorbed or transformed by Christianity to ease the transition. The cosmic battle between Perun and Veles—order and chaos, sky-god and trickster-serpent—was organically absorbed by the epic Christian opposition between god and the devil. But as seamlessly as that fits, it’s important to recognize that pagan Slavs didn’t view Perun as the “good guy” and Veles as the “bad guy.” Veles wasn’t an inherently evil figure or demon but one among a pantheon of deities worshipped by many of the same people. They were two sides of one coin.

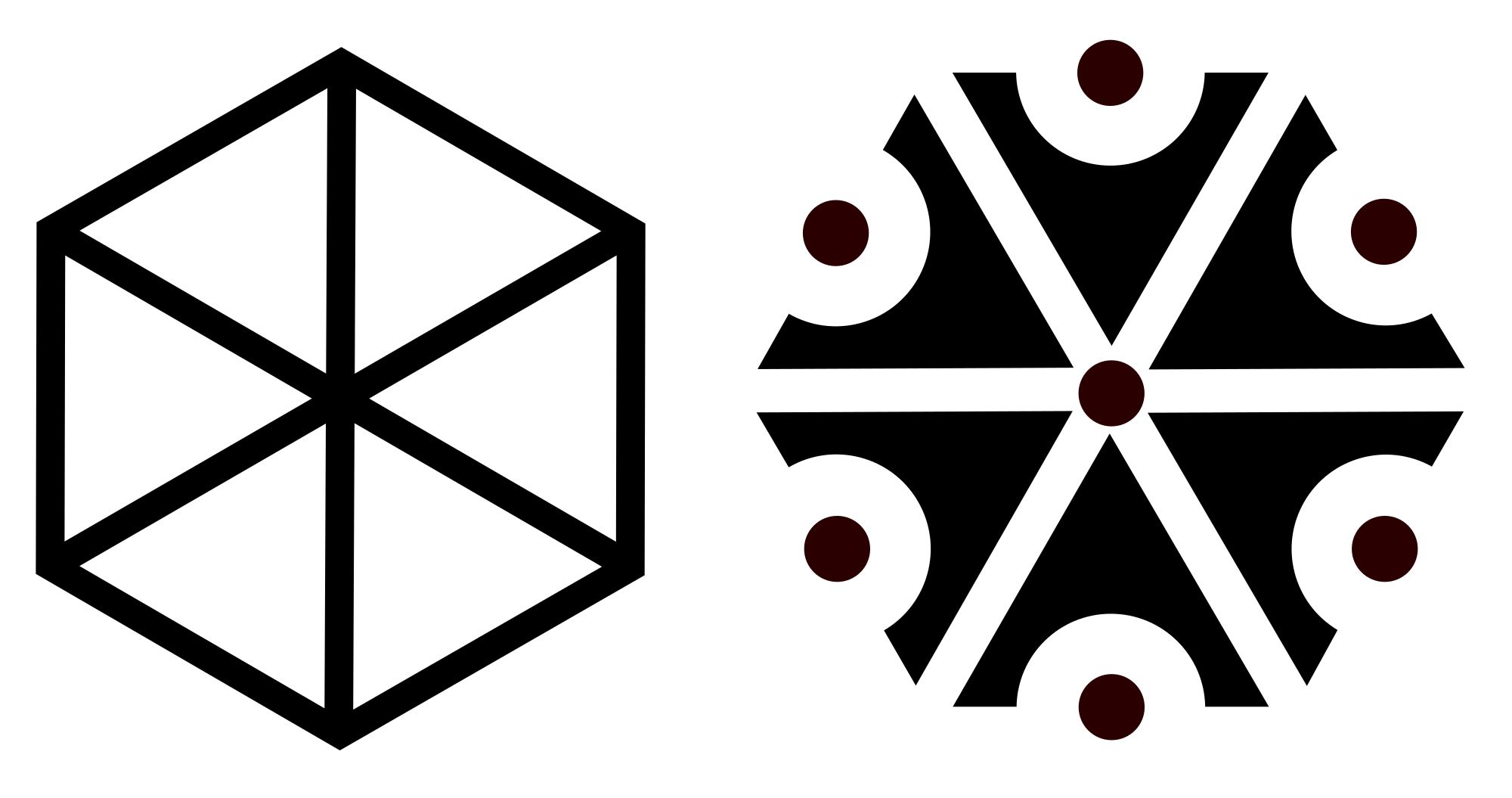

So what does this have to do with The OA? Take a look at the symbol of Perun:

The symbol of Perun, via Wikipedia

This six-sided symbol is a visual cue that crops up repeatedly in The OA. It’s reminiscent of the underground prison OA and her friends are trapped in, the fish tank in Homer’s NDE (and season 2’s clinic), the eerie location of the mystical Khatun from OA’s first NDE, the floor tiles in the Nob Hill house… this list goes on.

Hexagonal floor tiles in the puzzle house

Look closely at Khatun’s geometric enclosure

Throughout the series, the recurring polygons frequently appear as manifestations of captivity, capture, or enclosure. We are reminded of OA’s childhood nightmares of being trapped in an aquarium. Years later she’ll be a living science experiment, separated from the world by glass. When she jumps at the end of season 1, she arrives in a new dimension that once again conspires toward her imprisonment by Hap, this time in the Treasure Island clinic.

Now let’s look at the symbol of Perun’s mortal enemy, Veles.

The symbol of Veles

Rotate the symbol upside down and you have the letter A inside the letter O. OA.

If that’s not sparking your tin foil hat, let’s also look at OA’s choice of wardrobe.

One reading of OA’s decision to bring home the iconic wolf hoodie is its visual similarity to a sweatshirt Homer wore in the cell, and this is probably the in-universe reason she’s drawn to it. But remember when we called Veles ‘Lord of All Wolves?’ Bring together the symbol, the Russian origins, the affinity for the wolf, the NDEs as visits to an ‘underworld,’ and the frequent imagery of OA’s submersion in water, and we have a powerful case for OA as a representation or reincarnation of the god Veles. We even have a herpetology lesson and a line of dialogue in season 1 in which she references ‘shedding her skin,’ aligning with the other potent identifier of Veles as serpent/dragon. When making the parallel between the post-Christian Veles and the snake in the garden of Eden, we must also think of another image of Satan in Lucifer, one of the ‘original angels.’

We can recontextualize the series with the mythic weight of two primordial gods—OA and Hap (note the Percy/Perun linguistic similarities). The universe conspires to bring them together, despite OA’s escape attempts, which echo the myth of the chase. She can jump to new universes and still fall right into his lap. He can defeat or overpower her, but she always comes back, always resurrects. Hap imprisons. OA unlocks. Through intimate opposition and intertwined destinies, these two characters reshape one another constantly. The otherworldly lightness of OA’s presence frequently saves Hap from the ultimate evil he flirts with, unlocking an unexpected softness within him—cruel and cold as he is, the intricate sensitivities and deeply held desires of the character keep him on the edge. And OA, though we view her as a force of light, complicates her morality when she’s in Hap’s orbit. Like the two gods battling over the order of the universe, neither can be painted as fully good or fully evil. Rather we have the struggle of one character to preserve the power he’s always had, and the other finding a means of upsetting that power through her own agency. It’s not a retelling of this ancient myth—it is the ancient myth. Perun and Veles toil still, locked in a never-ending struggle across time, space, and planes of existence. Are the movements the remnants of an ancient ritual, evolving through time like the subjects do? Is there a path to escape for either character, or is an acknowledgement of their cyclical destiny and harmonious dedication to its continuance the best redemption we can hope for? How does Homer, the object of much of Hap and OA’s battle for control, complicate or uphold the mythic standards?

In a series as thematically rich as The OA, it’s nearly impossible to acknowledge every mythic influence, especially since many of the conclusions you can make are formed from a complex and interconnected web of cultures. Khatun is an interesting figure to use as an example, because her name is Arabic, and she wears something akin to a traditional sari, but the braille markings on her face correspond to lines of German poetry by the Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Later in the series she reappears as a Baba Yaga-type of figure, ice-fishing in a little hut and possessing the power of flight. She’s a tapestry, a patchwork quilt of culture and cosmologies.

For those who have puzzled over whether OA’s stories are true or simply a trauma coping mechanism, and for those who have painstakingly pieced together lines of dialogue, images, and references in the hopes of identifying the ‘correct’ way to interpret the series, perhaps this patchwork quilt is the best comfort to be found. We can acknowledge the dreamlike surrealism of our memories and our histories, reach for mythologized versions of ourselves across planes of reality, dance with death and our subconscious desires… Like the myths of disparate cultures blend and influence one another, our realities and our truths are flexible, ever-changing. As the tech mogul Pierre Ruskin puts it when describing the sea change mankind experienced when we first saw images of the earth from space, we’re in need of an overview, something akin to the new perspective gained by the few who’ve returned from the other side.

Sources

If you enjoyed reading this blog, check out some of my sources and inspiration. All images are affiliate links, meaning if you purchase the item, a percentage goes to the Midnight Myth Podcast. Thanks for your support!