A companion piece to Episode 20: Dark and Full of Terrors. Written by Laurel Hostak.

This week, on the Midnight Myth Podcast, Derek and I dove into a case study of the one and only Stannis Baratheon from George RR Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire series (and the HBO tv show Game of Thrones). You probably heard me call Stannis a POS multiple times-- and I stand by it. He's one of the most irredeemable garbage humans on that show, but he's different from the Joffrey or Ramsay archetype: a petulant sociopathic man-child with a born tendency toward grotesque violence. He's as close to a classic tragic hero as we get in Game of Thrones, with a close second being Jon Snow. We explored this a lot on this week's show, drawing parallels to some of the most immortal characters in tragedy (Agamemnon, Macbeth) and in Western history (Constantine). We compared beats of those narratives, and saw how closely the prince-who-was-promised lines up with those.

But Martin and the GoT showrunners have a lot more going on than aping classic tragedy. So I want to look closer at something Derek said on this episode-- that Game of Thrones often takes us to the place where classic tragedy meets existentialism. Sexy! Let's go!

What is existentialism? Here's the basic definition: a philosophical theory or approach that emphasizes the existence of the individual person as a free and responsible agent determining their own development through acts of the will. We'll get back to that.

I'm primarily going to look at Jean-Paul Sartre, a leading existential thinker of the 20th Century. One of his most prominent ideas was that human beings are "condemned to be free." By this, he implies that there is no creator, no master plan for our existence or predestined outcome for our time on earth. We are responsible for what we do--the noble and the ignoble, the fair and the unjust. Human beings cannot blame outside forces for their existence or their actions. We are "condemned" because there is no heavenly father figure guiding us in the right direction or the wrong. Free will means the onus is on us. All puns intended there. Zing!

From here, we can imply another component of existentialism from Sartre, that "existence precedes essence." It's similar to the above point, but a step further. Essence, in this equation, amounts to meaning or purpose. If a thing's essence precedes its existence, then it was brought into being to serve a distinct purpose. Like someone creating a paper cutter. The creator says "I need a thing to cut paper," and from this essence, the paper cutter is born. Human beings, according to Sartre, are the reverse. Here we are. We exist. And no matter how many religions or philosophies take on the big question of "why?", existentialism will always drive home the futility of this question. We were not formed by a creator out of a desire to serve a purpose on earth. We got here, and now we're on our own in the search for a deeper meaning. Existence is a given, so now what? In some ways, it's a liberating idea, to know that we have the power to shape our own essence, to forge meaning in our own lives. But it's also scary--and that's why Sartre says we're "condemned to be free." Because if you look close enough, you can slip into nihilism. Our existence is meaningless.

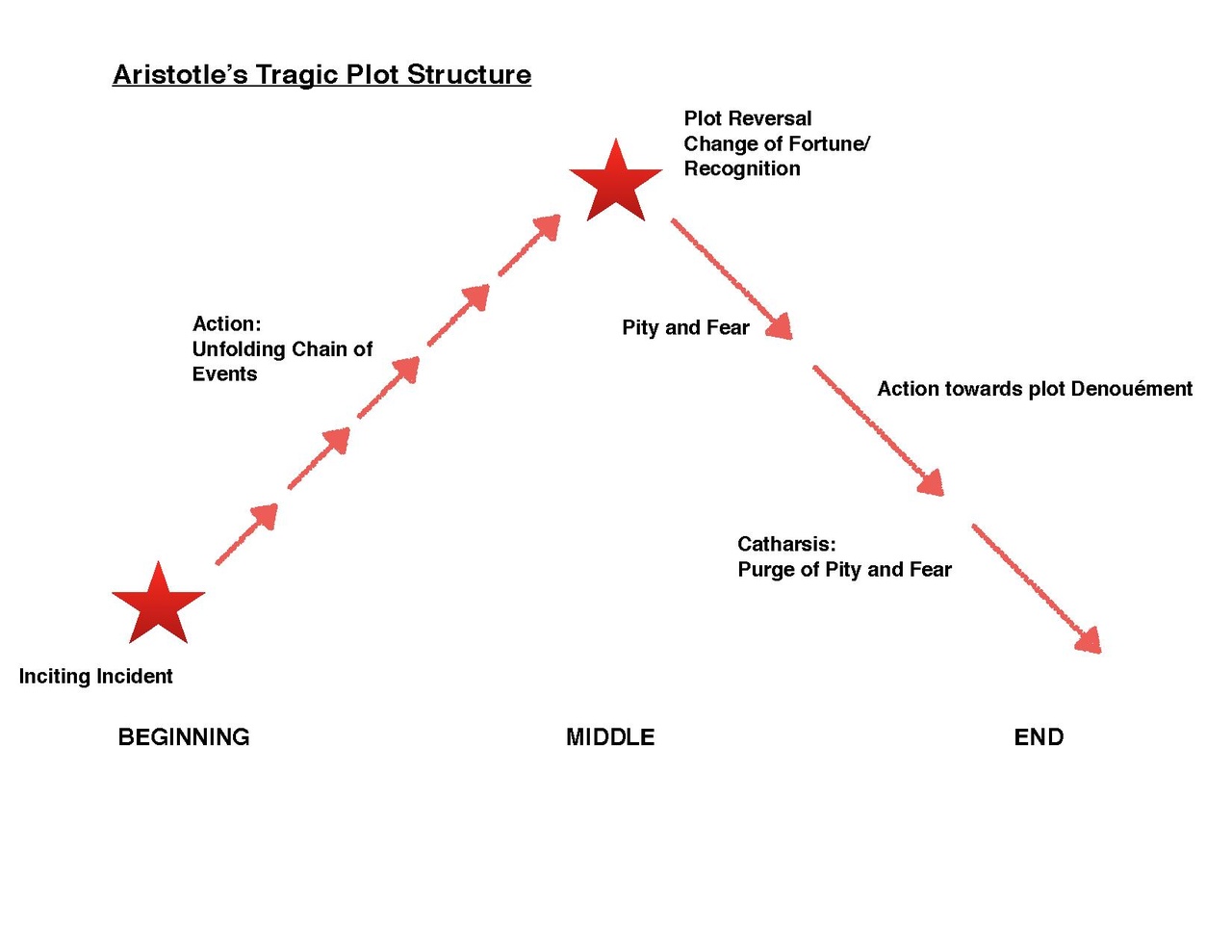

So where does tragedy enter the picture? As a genre of drama or storytelling, tragedy has a simple definition: a play dealing with tragic events and having an unhappy ending, especially one concerning the downfall of the main character. Key point: downfall. Aristotelian plot mapping gives us a tragic structure that looks a bit like the outline of a mountain. It goes up, and then it goes down. It follows the path of the tragic hero, who arises to a great height, then tumbles back down in disgrace, usually due to a "tragic flaw," an incredibly specific character weakness that directly leads to their fall. More often than not, this flaw is hubris, which manifests as excessive pride in defiance of the gods in Greek tragedy.

Aristotle's tragic plot structure

Hubris, I think, is the heart of the genre. All of our famed tragic heroes from Greece to Elizabethan England suffer in some way from a lack of sufficient respect for the power of the gods or the reigning ontology (see my blog post Outrageous Fortune for more!). They frequently subscribe to an overabundance of human pride, sometimes equating themselves with divine figures or believing themselves immune to divine will. Oedipus' downfall is a direct result of his attempt to escape the fate ordained for him by the gods. Macbeth's downfall is a result of his ascent and destruction of the social ladder put in place by god. Agamemnon, in the story we related this week, is struck down for killing a stag sacred to the goddess Artemis. Tragedy becomes an exercise in man's futility in the face of the divine or other cosmic or natural forces. The very nature of tragedy implies the existence of gods or a greater power, the wrath of which is to be avoided. Tragedy is predicated on a belief system that, unlike existentialism, is somewhat shackling. We have no control over our actions or destinies; we live at the mercy of larger forces. And if we have no control, why even continue our search for the essence?

It strikes me as I write this that both sides of this coin seem, at times, to teeter on the edge of nihilism. How classic tragedy and religion seem as much of a scream into the void as Sartre's play No Exit. If you follow each to its furthest conclusion, it's hard not to arrive at "everything is meaningless."

But here, right at the edge of meaninglessness, lies Stannis Baratheon.

Made in the image of Agamemnon and the archetypal tragic hero, is the reluctant man who would be king. Bolstered by a vague prophecy and a priestess of the Lord of Light, Stannis leads an army of supporters of his claim. We watch as Melisandre demands greater and greater sacrifices in the name of the god from whom she receives her power. We watch Stannis take on more and more difficult challenges and pay higher prices in the quest for a title he might never have pursued without the spur of others. Stannis hits every milestone you would expect from a Greek tragedy on his long climb to the top and his swift fall from grace. And yes, there are gods and supernatural forces at attention. But when Stannis, backed into a corner and given a way forward into battle, sacrifices his daughter, Shireen, to Rhllor, divine fortune does little to secure victory. In fact, Rhllor melting the snow and clearing a path to Winterfell is inconsequential. Half of his men up and leave because they've witnessed an atrocious act and can no longer march under morally bereft banners. It's not defiance of the will of god that dooms Stannis, but defiance of the laws of man.

If we had to ascribe a tragic flaw to Stannis, we'd probably land on something more complex than hubris. In fact Stannis is the opposite of tragic heroes whose pride gets the best of them. Even if he's conflicted, he obeys the will of the god who has named him the future king. The problem is that he is a cocktail of moral hypocrisies, with no consistency in his understanding of right and wrong, the greater good or the higher morality. He speaks in moral absolutes that often directly contradict each other, sometimes in the same breath, always serving to justify his actions in the moment. He is existence before essence personified. Make the decision, then look for the meaning--even if that requires some ethical gymnastics, to which Stannis is no stranger.

At times, I think Game of Thrones plays up these dualities and conflicts between tragedy and existentialism to point to another school of thought: Absurdism. This philosophy refers to the conflict between the human tendency to seek inherent value and meaning in life and the human inability to find any. As Stannis lies dying, we have to assume he reflects on the actions that led him here, and we have to assume he feels regret. What was it all for? What did he achieve by hurting so many? What meaning has he found in this existence? This has a greater pattern in the show. How many times did you, as a viewer, become attached to a character or a house, only to witness its ultimate destruction? What was the greater purpose of Ned, or Robb, or Oberyn? And did Martin, as we like to jest, simply kill them off to shock or damage us?

As viewers of this universe, we have the unique privilege of observing the many intricacies of Westeros and its characters. We get to zoom out and see the patterns. We watch the ignoble deaths and humiliations. We still search for meaning in the narrative (we're only human), but we've begun to recognize it as a Sisyphean task. We are coming face to face with the fact that there is no cosmic force that governs or steers this ship. That men are messy and make poor decisions and often die before their arc is complete. There isn't always catharsis. Like reality, it's absurd. It's a joke.

In some ways, Game of Thrones is little more than a comedy.

For more on Existentialism, read Jean-Paul Sartre's Being and Nothingness.

For more on Absurdism, read Albert Camus' The Myth of Sisyphus.